A petrochemical 'ecosystem'

Pennsylvania's extensive fracking network hiding in plain sight

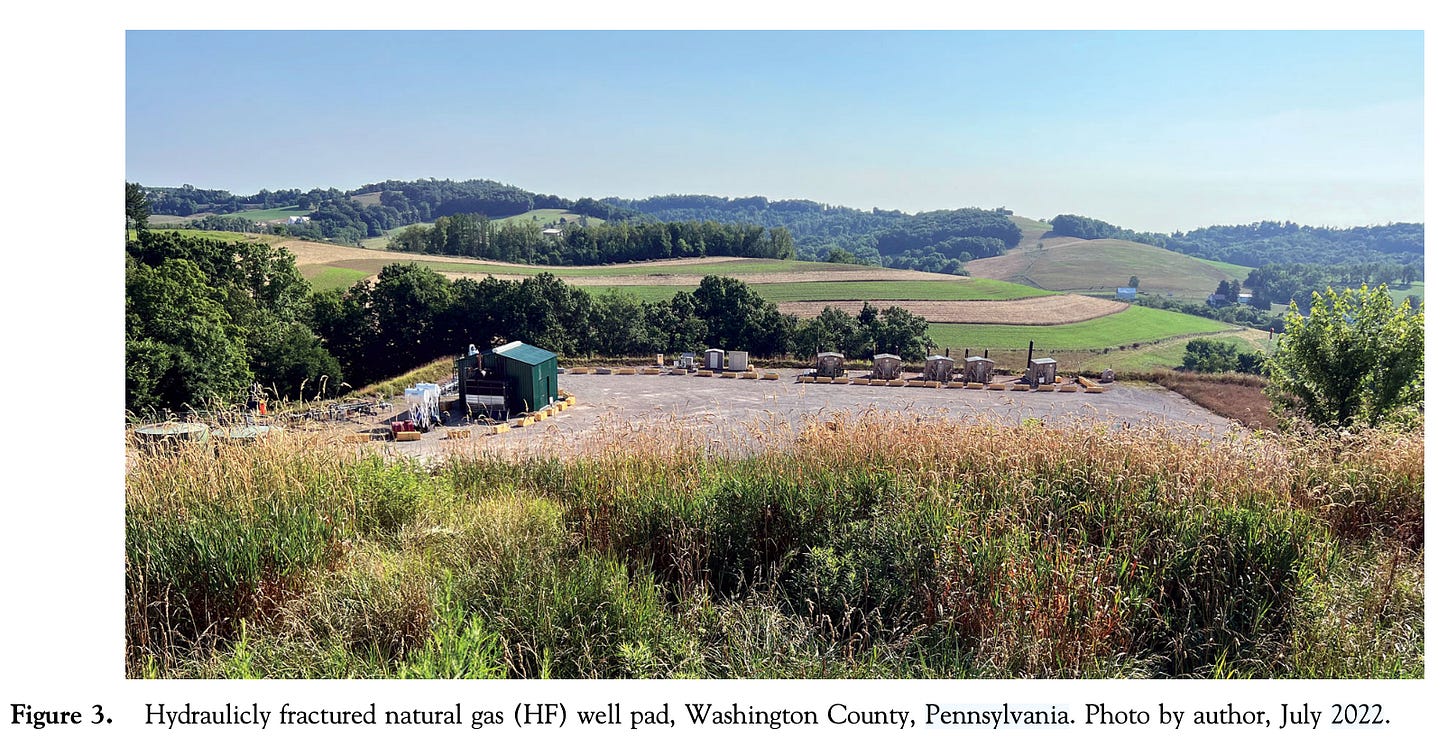

If you spend any time in The Keystone State, then you're likely to take in the idyllic scenery of the northern Appalachians. Pennsylvania's rural areas are landscapes of rolling hills, fields, and tree-covered mountains. Forests cover approximately 60% of the land in Pennsylvania, along with over 7 million acres of agriculture among some 53,000 farms. What you may not notice, though, is a sprawling network of petrochemical infrastructure.

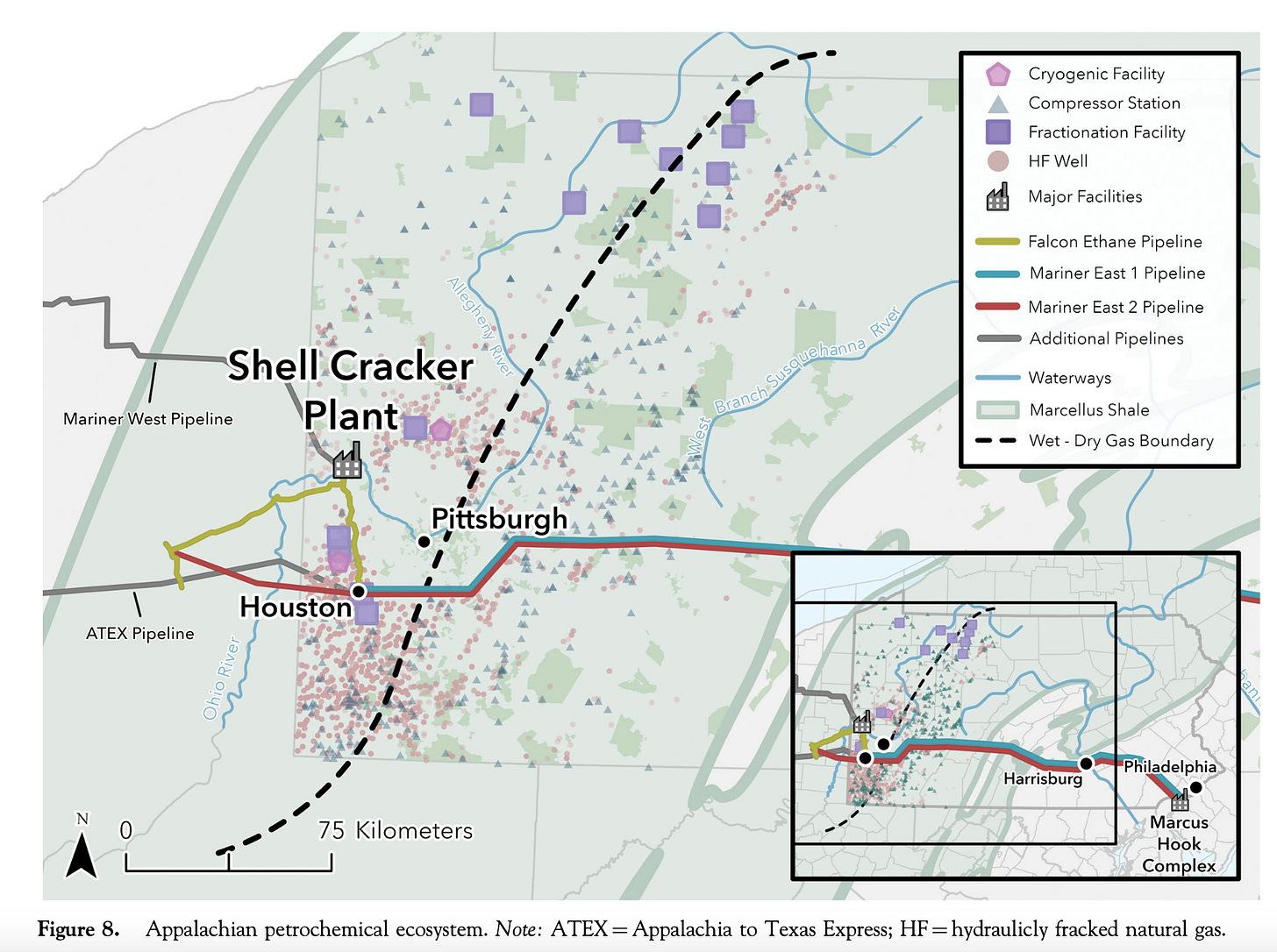

New research by Penn State geographer, Dr. Jennifer Baka, identifies an interlinked petrochemical "ecosystem" across the state. The network is dispersed across space, and often concealed from Pennsylvania communities in both specific location and its full extent.

In 2023, Shell Chemical Appalachia (a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell) opened a multi-billion-dollar ethane cracker plant near Pittsburgh, in southwestern Pennsylvania. The plant primarily outputs polyethylene nurdles, which are a required component of plastics manufacturing.

While the Shell plant represents one of the largest private investments in state history, it is only one part of a much broader ecosystem that supports it. This ecosystem has disparate impacts across Pennsylvania, and communities are expressing concerns about the complexity and opaqueness around this growing network of fracking infrastructure.

Dr. Baka's research combined quantitative and qualitative methodology to to illuminate the scale of Pennsylvania's petrochemical ecosystem, revealing over 20,000 sites of infrastructure. Theses sites include hydraulically fractured natural gas wells, compressor stations, pipeline inspection gauges, pump stations, natural gas processing facilities, pipelines, and export terminals. Some of these are large and conspicuous facilities that are easily identified, but others are small, making them harder to detect across the landscape.

Are you interested in how society might move beyond purely extractive relationships with the environment? Check out my recent piece, Ecologizing Society, the first of an upcoming series of essays about how we could do that.

The study also reveals some of the reasons communities have had difficulty obtaining information about the full size of the network. There is no central repository of data that fully accounts for fracking infrastructure, requiring interested parties to access multiple sources of data that are often difficult to find, complicated to navigate, and either incomplete or inaccurate.

Understanding the full scope of the petrochemical ecosystem is more than just an academic exercise. Each component requires its own permit and has its own associated environmental impacts. For example, hydraulically fractured natural gas wells may disrupt the subsurface of nearby properties without communities' knowledge. Compressor stations remove "produced water", or water occurring in hydrocarbon streams, which often contain toxic chemicals that can contaminate groundwater. Pipelines pose a threat to community property if and when government agencies use eminent domain to acquire land for pipeline construction.

The Shell plant near Pittsburgh is estimated to emit 522 tons of volatile organic compounds and 348 tons of nitric oxide per year, which could be the equivalent of adding 36,000 cars to the region annually. When volatile organic compounds and nitric oxide combine in certain conditions, it can create ground-level ozone. This would add ozone to the air of a region in Pennsylvania that already exceeds levels that pose a risk to public health. What's more is that government regulators allowed Shell substitute nitric oxide emission reduction credits for volatile organic compound reduction credits. The substitution allows Shell to achieve air quality compliance on paper while continuing to emit pollutants into the air at the Pennsylvania plant.

Difficulty in understanding the full scope of the petrochemical ecosystem also means difficulty in quantifying its aggregate environmental and health effects.

"This is why I argue for conceptualizing the plant as an integrated industrial ecosystem—to facilitate cumulative impact analysis," said Dr. Baka. Part of the motivation for the study was to make the network visible to Pennsylvania communities. Additionally, the work revealed connections beyond the state, linking the ecosystem to the US Gulf Coast, Canada, and Europe.

Dr. Baka is also working on a second stage of the project that will create additional maps and resources for the communities concerned about the impacts of petrochemical infrastructure. She notes that it's too early to know if and how this research might motivate communities to participate in fracking governance processes, but community members are nevertheless grateful for the research into the full scale of Pennsylvania's petrochemical ecosystem.

Wow, so glad I found your page this morning. As someone who lives in a oil and gas dominated ecosystem I wish someone would put together a study like this here.

Excellent read, making it very digestible & easy to understand the problem and how they manage to hide it in plain sight.