Cocoon Spotting: Giant Silk Moths in Winter

By Bill Rhodes

The following is a guest essay provided by Northern Woodlands Magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org. Be sure to subscribe to Brief Ecology for more ecological writing and essays!

Cocoon Spotting: Giant Silk Moths in Winter

By Bill Rhodes

Late fall and early winter are the best times of year to spot giant silk moth cocoons in New England. Perhaps you’ve seen these creatures in the summer, fluttering by your porch light in the evening or resting on your garage wall in the early morning after spending the night at its light.

These large, showy moths in the family Saturniidae live only briefly as winged adults, are strikingly colored, and, as moths go, are huge. Caterpillars hatch from eggs in the late spring and summer and eat voraciously before spinning silken, papery cocoons. (Species in Saturniidae are unrelated to the domestic silk moth, which is bred for silk.) They may spend as many as 10 months pupating, emerging to mate and lay eggs before dying, as they do not have mouthparts equipped for eating.

Four species of giant silk moths are common in the Northeast. A fifth species, the Columbia silk moth (Hyalophora columbia) is uncommon but can be found in northern Vermont and New Hampshire.

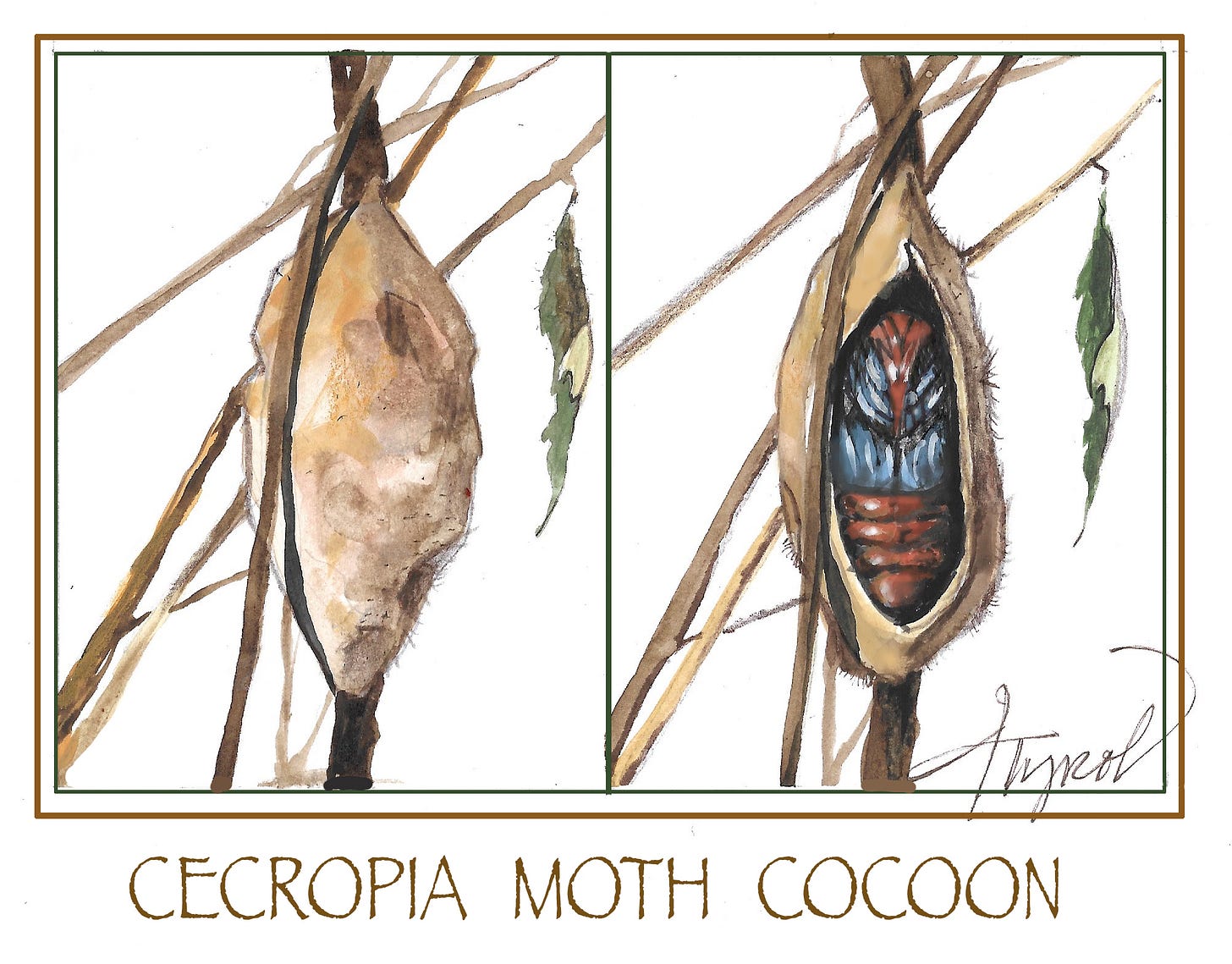

The largest is the cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia) with a wingspan that can reach seven inches, making it the largest moth in North America. Its abdomen and thorax appear furry and are bright red with contrasting white bands. Each of its four wings has a reddish crescent with a white center, rimmed with red, white, and pinkish bands.

Cecropia cocoons are unassuming. They are drab, papery brown, and are meant to blend in with the tree branch or trunk they are firmly adhered to. Caterpillars feed on maples, cherries, and birches, so cocoons can often be found on these trees. It is best to look up into the tree at just above eye level, framed against the sky, and search for a brownish, papery “bag” clinging to a branch. Inside is a large pupa, slowly turning the fat green caterpillar into a winged adult. The nondescript appearance is purposeful – rodents, particularly squirrels, will eat the pupa in the cocoon, so blending in raises the chances of survival.

Another large silk moth, about six inches across, is the Polyphemus moth (Antheraea polyphemus). It is tan colored with blue shading, and its hindwings sport prominent blue eyespots, used to trick and deter predators.

Polyphemus caterpillars feed on oak, birch, and elm, among a number of hardwoods, and wrap their cocoons in a leaf or two while they spin for extra camouflage. Unlike the papery brown sack of the cecropia, their cocoons are whitish or cream colored, with the silken threads clearly visible. They may drop to the ground when the leaves fall, so it is good to look among the fallen leaves below the trees, but I have always found their cocoons a short distance away, clinging to leaves still attached to shrubs or taller grasses.

Perhaps the most striking giant silk moth in our area is the luna moth (Actias luna). Though it is smaller – at about four and a half inches across – its pale green color and gracefulness make it stand out. Luna moth cocoons are wrapped in tree leaves, so when they fall to the ground, they become hidden among the leaf litter. It’s best to look beneath sweet gum trees – a favorite food tree – and use a stick to move the leaves about, looking for a brown, thin-walled, oval-shaped cocoon wrapped in a brown leaf.

Finally, there is the smaller promethea moth (Callosamia promethea) which generally measures about four inches in width. These moths are dimorphic as adults: males are dark brown on their upper side, and females look similar to the multicolored cecropia moth, with prominent eyespots on their forewings. Caterpillars feed on tulip and sassafras trees, as well as spicebush, and spin their cocoons at the tips of branches, reinforcing a leaf’s petiole with silk, allowing them to hang down throughout the winter, wrapped in that leaf. One winter I came upon a spicebush festooned with promethea cocoons waiting to emerge in late spring.

To add novelty to your winter walks, try cocoon spotting. Be prepared to search for a bit to find their hidden, silken lairs wrapped in fallen leaves, attached to branches, or hanging from bushes – and know that come spring and summer, they will produce majestic giant silk moths.

Bill Rhodes is a writer and retired life sciences executive. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.