Leaf and Litter

New research on forest nutrient cycling

It's been another week. There's been more disturbing developments from the federal government, but I'm trying to strike more of a balance in these newsletters, between the bleakness of the current situation in the US, and this week highlighting some cool, recently published research conducted outside the US.

Margarita Fernández is an ecologist here at Penn State, and her and her co-authors recently published a paper on the effects of nutrient enrichment to forest leaf decomposition. Check out my highlight of the research below, and if you find these topics interesting, be sure to follow Marga on Instagram (@pratellina). She does good science communication about forest ecology.

The Eco-Update #4

National Parks saw record visits in 2024, but the National Park Service was told not to publicize it

National park visits totaled a record 332 million in 2024, representing a 2% increase from 2023, but the National Park Service was told to not promote this increase. Suppressing this statistic only makes sense if you don't want to receive more bad press after just firing over 1,000 NPS employees, or if you're trying to sell of vast amounts of public land to private developers (both of which the federal government are recently responsible for doing). Our National Parks provide billions in economic, health, and environmental benefit to the public. But what's the value in that when they could be destroyed in order to make a few rich people a little richer?

Retired hens fertilize olive groves, boosting yields and managing waste

What does sustainability look like? Maybe it's retired hens clucking and pooping around olive trees. A project in Cyprus found that letting hens that were past their egg-laying years roam free in their olive groves boosted their yields and reduced food waste. Inputs of organic material into the soil are an important component of agricultural systems, so this makes sense. And seriously addressing climate change requires that we find second acts for livestock instead of just slaughtering them for consumption, which only contributes to overproduction and more emissions.

UK cities are banning ads for airlines, SUVs, and fossil fuels

While the US government is busy sticking its head in the sand to ignore the realities of climate change, cities in the UK are taking action. Edinburgh and Sheffield have banned advertisements for fossil fuel companies like Shell and BP, and also on SUVs and airlines. In doing so, they've joined cities like Toronto, Montreal, and Stockholm in taking bold action against the companies most responsible for causing global climate change.

EPA is cutting regulations that keeps US air healthy to breathe

Who needs to breathe when there's money to be made? The new EPA administrator announced that they're going to cut many of the environmental regulations that played a vital role in landmark improvements to US public health. The only thing this will accomplish is allowing industries to pollute our air more freely, and thus line the bank accounts of their billionaire shareholders with even more profit. This will not improve the lives of working Americans.

Leaf and Litter

When I was first studying ecology as an undergrad, I had a professor who said that trees make their own habitat. I hadn't ever really thought about it in those terms before, but that's exactly what happens when leaves fall from deciduous trees every year (becoming leaf litter) and then decompose into the soil layers. We don't tend to notice them once they fall to the ground, but leaves are still critical components of the nutrient cycle at that stage.

The structure and chemistry of the soil in many forests is maintained through this regular input of organic material. In this way, trees produce a favorable habitat for themselves to grow in. But this maintenance is dependent on the regular cycling of nutrients at consistent rates. Globally, many forest ecosystems are threatened by excessive nutrient additions. These additions can impact leaf litter quality and decomposition by changing the dynamics of plant nutrient cycling, and also cause cascading effects across trophic (food web) levels. Given the scale of nutrient additions globally, it's critical for us to understand these impacts in order to preserve the functioning of forest ecosystems.

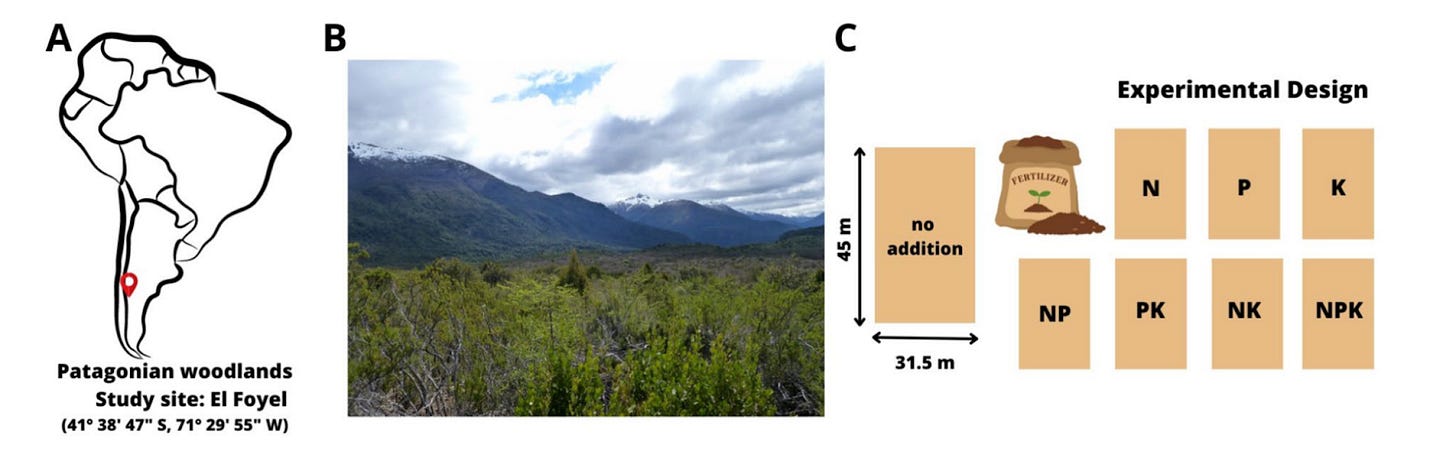

Recently, some colleagues of mine published research on these topics. Margarita Fernández, who led the work, conducted an experimental fertilization study in a northwestern Patagonian woodlands. Unlike North America, South American forests have not been exposed to high nutrient additions, making Patagonia an optimal location to conduct this kind of research.

Fernández and her team added different combinations of nutrients to a series of plots to analyze what effects the additions had on leaf litter quality, decomposition, and the activity of soil microarthropods (small bugs) involved in decomposing organic material. The study objective was twofold: 1) to determine which combinations of nutrient additions impacted leaf litter quality, and 2) to assess whether there were effects on microarthropod-driven decomposition.

As a result of these nutrient additions the researchers found expected impacts, but also some surprising ones. In general, litter quality was strongly influenced by the addition of nutrients. While this was not surprising, more interesting was that decomposition changes via microarthropods were more strongly associated with microsite conditions than changes in leaf litter quality. More specifically, nitrogen additions strongly impacted leaf litter quality but did not directly impact the microarthropod community, while phosphorus additions did impact microarthropod-driven decomposition.

So, there's a few interesting things going on here. One is that the researchers' findings challenge the prevailing consensus that microarthropods play a positive role in decomposition under nutrient-enriched conditions. The patterns the researchers observed were context-dependent, being driven by the microsite conditions driven by nutrient additions rather than changes in litter quality. This suggests that interactions between trophic levels, in the context of existing conditions, plays a role in shaping these ecosystem functions.

This has important implications for something I've been thinking about a lot lately, which is the ongoing quest in the ecological sciences for generalizable theories. Empirical studies, like the one here led by Fernández, are increasingly finding patterns that challenge those predicted by theoretical models. I think the authors of this study are absolutely correct in stating that context-dependency is a large part of the story in determining ecosystem function. And while that might be a topic for another day, these results nonetheless have interesting implications for the biogeochemical models we use to predict nutrient cycling.

About the research, Fernández said, "Forest soils host immense biodiversity crucial for long-term productivity, yet their functional roles are often understudied in many ecosystems around the world. In many cases, soil fauna coevolved with plants to process their litter. However, human interventions can disrupt these balances, leading to declines in soil fauna and the ecosystem services they provide. Quantifying and describing such changes is crucial for soil health and forest productivity worldwide."

Furthermore, she stated that one particularly interesting finding was that while these organisms are adapted to enhance decomposition under nutrient-limited conditions, the balance shifts when fertilization is introduced, with long-lasting impacts.

At a time when ecosystems are changing rapidly, it’s crucial that we understand how our own actions are influencing these changes. That's why the work of researchers like Margarita and her co-authors is so important.

I think I get the gist of your article and will look for more information. I am also into in a related issue. I live in a small bit of oak forest that did not burn in the Eaton Fire. I am looking for info about how to reseed the terribly scorched soils of the San Gabriel mountains.