Leaf fall, tree bark, and the many faces of sugar maple

On Bark #0 and #1

Leaf fall and tree bark

As autumn gives way to winter, a walk through the woods reveals that the forest is becoming a different place. The leaves of the trees fall, greens fade to browns, birdsongs quiet, and the forest suddenly seems more like a forgotten ruin than a living cathedral. But something remains. There is still some life in the forest, so omnipresent that it is often reduced to the forest itself rather than the idiosyncrasies it displays or the different trajectories it’s taken. This life is the trees. The trees remain no matter the season, and although their leaves fall every year, their bark is always there.

Tree bark is often overlooked. People may realize that the bark of trees differs between species, but those characteristics take a back seat to the size, the shape, the leaves, and other more showy aspects of trees. And yet, the bark of a tree is always right there in front of us. To recognize tree bark, to pay attention to it and examine it, opens up an entirely new way of exploring and experiencing the forest.

That’s what On Bark is: an ode to all the different shades and shapes of tree bark. No two are alike. Trees are like people, in that way, and places. They are unique and similar at the same time. And so not only is On Bark an exploration of trees, it’s also an exploration of the place, time and meaning of each encounter. Maybe that doesn’t make much sense yet, but it will later. Or maybe not. There’s something unknowable about the forest, isn’t there?

What is tree bark?

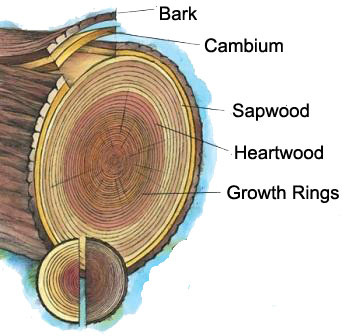

While the essays of On Bark will not be solely about the scientific characteristics of tree bark, it will be helpful to have some basic knowledge about what the bark of a tree actually is. If you picture the stump of a recently cut tree, the bark is the outermost layer that can be easily detached from the inner layer of wood. A thin layer called the vascular cambium separates the inner wood from the outer bark. The vascular cambium produces xylem (the wood of a tree) to the inside and phloem and bark to the outside (Figure 1). The xylem and phloem are the circulatory system of the tree.

The bark itself is composed of several layers that are collectively known as the periderm. The vascular cambium produces new layers of cells each year, known as the annual rings. This process also produces new layers of periderm, and the characteristics of the bark are determined by how different species of trees accommodate this new outer growth. Some form ridges as the layers break and stretch, and some continuously grow the outer layer at the same rate, producing the smooth bark of American beech.

These ridges and wrinkles protect the inner layers of cell formation, and are also identifying features of different species. Trees, however, also need to exchange gases with the atmosphere along their stems and branches. Small pores called lenticels allow them to do so, and these also come in a variety of shapes and sizes.

Collectively, these characteristics allow a keen observer to identify different species of trees based solely on the bark. What makes this slightly more challenging (and interesting) is that the bark of some species can change dramatically over the course of a tree’s life. For example, I’ve seen bark on maples that looks like both ash and tulip, so there’s a fair bit of experience required to identify trees based on bark alone.

Tree bark appearance is also a product of many external factors. Different species have evolved different strategies for dealing with extreme climatic conditions, energy production, temperature regulation, pest infection, wildfire, and wound healing. In this way, tree bark reveals the long history of evolutionary time, and also the history of individual trees.

Why touch bark?

Maybe this all begs the question: Why care? Why touch bark, literally, or metaphorically, or spiritually, or in any other way. I’ve already mentioned the ways that bark can be used to identify tree species, and maybe that’s reason enough for some, but I don’t think it’s the only reason.

Historically, the bark of trees has been used for medicinal purposes, different species believed to have different properties according to the tannins and resins and other metabolic products they contain. While On Bark is not in any way meant to contain medical advice, I will explore the historical relevancy of different species with respect to the uses of bark.

And history is important beyond medicinal use. People have been living among trees as long as people have been around. We have many, many stories and myths about trees, and I find where folklore intersects with tree characteristics to be a fascinating insight into human culture and history.

Lastly, paying attention to the bark of trees creates a richer, more diverse experience of the forest. Knowledge about tree bark enhances one’s ability to read the forest as a text, a record of time and space.

On Bark will explore all of these aspects, and more. So if you’re someone who likes spending time in the woods, or thinking about the forest, or engaging with the long lives of trees, then On Bark is for you. Join me on an exploration of an often-overlooked aspect of nature.

The Many Faces of Sugar Maple

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Brief Ecology to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.