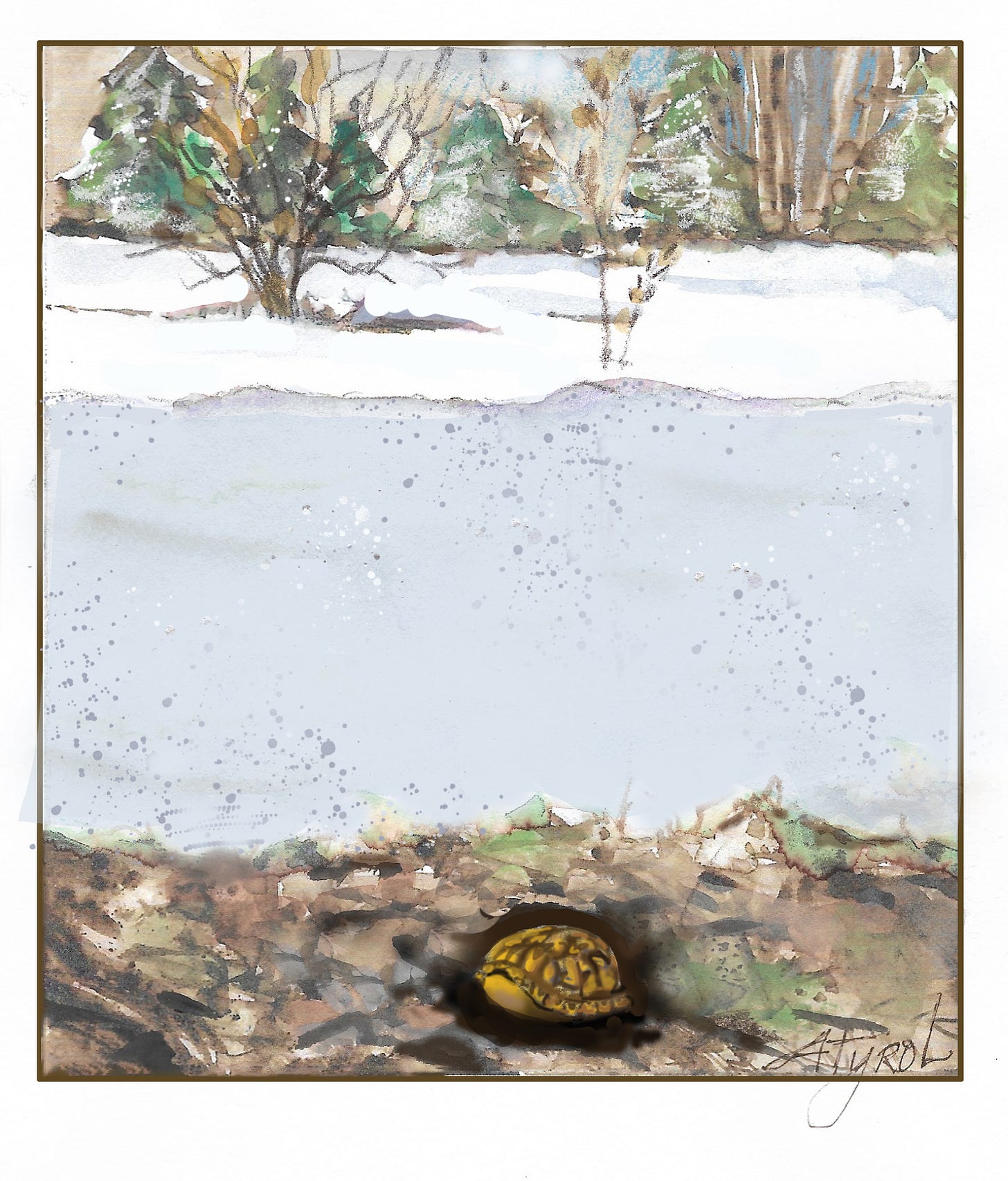

Life Beneath the Ice and Snow: Turtles in Winter

By Loren Merrill

The following is a guest essay provided by Northern Woodlands Magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org. Be sure to subscribe to Brief Ecology for more ecological writing and essays!

Life Beneath the Ice and Snow: Turtles in Winter

By Loren Merrill

For hundreds of years, people believed that, come autumn, barn swallows would dive under the surface of ponds and lakes, swim to the bottom, and bury themselves in the mud for the winter. We now know better – swallows, along with thousands of other avian species across the globe, undergo seasonal migrations – and the idea of birds spending the winter buried in mud at the bottom of a pond seems laughable. But there are other vertebrate organisms that do exactly this: some water turtles, such as painted turtles and common snapping turtles, search out the soft substrate at the bottom of ponds, rivers, and lakes, and burrow down into the mud. They survive by dramatically reducing their metabolic rates – in some cases as much as 99 percent – which allows them to survive for months in low oxygen (hypoxic) and no oxygen (anoxic) conditions. This form of reduced metabolic activity in winter is known as “brumation” in reptiles and amphibians.

Other water turtles, however, are unable to survive anoxic conditions and thus cannot bury themselves in the mud. Northern map turtles, for example, winter below the ice but do not shut down metabolic activity entirely. Recent research has shown they will congregate at shallow locations (1 to 2 meters depth) near the bottom, where they spend months alternating between low levels of activity and standby mode. Northern map turtles, like most other northern water turtles, perform all necessary gas exchange through highly vascularized regions of their skin during the winter. However, if they are wintering in non-moving water, they can deplete the oxygen from the water surrounding their bodies, necessitating some movement. Smooth softshell turtles, for example, do “push-ups” when overwintering under the ice, and scientists speculate that this action breaks up the oxygen-depleted layer around the turtles. Similarly, northern map turtles occasionally move around, presumably to disturb the hypoxic water layer. Researchers also theorize the turtles may be congregating in areas with relatively higher dissolved oxygen levels, which helps them meet their oxygen needs.

Unlike their water-inhabiting cousins, eastern box turtles spend the winter on land in shallow burrows. These burrows provide some degree of protection against the cold, but researchers have found that the turtles may still experience subfreezing conditions.

Eastern box turtles have a few tricks tucked up their shells for coping with this challenge; they can supercool their bodies to approximately 30 degrees Fahrenheit for short periods of time, and when temperatures drop sufficiently low, they can withstand having their bodies freeze, like wood frogs. In both species, this feat is accomplished by shunting much of the water in their bodies into extracellular spaces and flooding their cells with glucose. These actions protect the cells from freezing, which would lead to the death of the animal. Wood frogs can freeze solid for an entire winter, all organs going into a state of suspended animation, including the heart. The freeze-tolerance capabilities of wild box turtles are not well known at this point, but a laboratory study published in the Journal of Experimental Zoology in 1990 found that they can handle freezing for at least 73 hours, and that up to 58 percent of the water in their bodies can freeze. Come spring, these turtles begin making short trips out of their burrows to look for food, and to catch some rays.

Adult box turtles aren’t the only turtles to overwinter on land: in many northern species, late-hatched young remain in the nest through winter. Freeze-tolerance appears to be rare among turtles, so how do hatchling turtles that overwinter in the nest survive? The data are sparse, but many of these species appear to use one or more of the following strategies: they depend on conditions within the nest chamber to remain above freezing; they can supercool their bodies to temperatures below freezing (but only if there is nothing touching the hatchlings’ skin, which would induce the formation of ice crystals); or they have some ability to tolerate freezing for short periods (baby painted turtles can do this). Not all late-hatching turtles that overwinter in the nest survive – some do succumb to the cold – but it appears to be a strategy many species use at least on occasion.

It is easy to forget about the shelled members of the ecological community when we wander the winter landscape, but they are here, some enduring conditions as extreme as those of the imagined mud-bound aquatic winter swallows.

Loren Merrill is a science writer and photographer with a PhD in ecology. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.