The Eco-Update #11

Dispatches from the planet.

Why only pollute the Earth when we can do it in space too?

You might not think that sending satellites to space causes pollution, but it does. Most of the satellites that we send into what's known as Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) end up burning up in the planet's atmosphere, depositing much of the metal as a vapor where it collects over time. This is usually the intention, because it's cheaper than using more fuel to push them into a higher orbit once they stop functioning.

With the relatively few satellites we've launched in the past this issue hasn't been a major cause for concern. But in 2019, SpaceX launched its first "megaconstellation" of satellites, known as Starlink. This launch put 60 satellites (all with very short lifespans) into Low-Earth Orbit, and SpaceX alone plans to launch 42,000 into orbit, which would dramatically alter the chemistry of Earth's atmosphere. Some scientists suggest the added aerosols could deplete atmospheric ozone.

Adding this many satellites to orbit poses other risks as well. If objects in orbit collide, the resulting debris can cause more collisions, and could eventually create a feedback loop of self-propagating collisions, rendering Low-Earth Orbit unusable. This is what's known as the Kessler Syndrome, and is what the film Gravity was loosely based on. More satellites in orbit also increases light pollution and reduces our ability to detect dangerous asteroids.

So why would SpaceX (and other companies) send so many short-lived satellites into orbit? Because there's money to be made. Waste and pollution are by-products of capitalism. In fact, the entire reason private corporations are increasingly interested in entering outer space is that we've nearly exhausted all the places on our own planet to externalize the destruction of profit-seeking. We don't need more satellites in orbit. We need less capitalism on Earth.

More attacks on science

The Trump administration's attacks on science haven't been in the news as much recently, but they are still very much ongoing. So far the administration has terminated an estimated over 100 climate change related grants from the National Science Foundation alone, cutting off as much as $200 million from universities and researchers across the county.

These projects included research on clean energy transitions, measuring methane emissions, and the impacts of climate change on marginalized communities. Cutting this research is the worst possible decision at a time when we're already dangerously overshooting our climate change goals.

Of course, the Trump administration doesn't want the public to know about climate change, or its effects, even though we can see it with our own eyes. They're attacking any research that doesn't align with their anti-intellectualist agenda.

GrantWatch is a project aimed at tracking the funding cancellations. They've published a public database that anyone can search. I checked it myself and found that as many as 25 ecology-related NSF grants have been cancelled. Considering we're in the midst of a global biodiversity collapse, the consequences of shutting down research are going to be severe.

Speculative Ecologies

Last week a recent paper of mine was published in Literary Geographies. This was a side project which explored the ways the nature and ecological anxiety are represented in speculative fiction.

Ecological anxiety, in response to environmental degradation, is an increasingly popular theme in fiction. The premise of my paper is that the ways nature is represented reveals how society relates to nature, both challenging and reinforcing the structures that cause environmental degradation.

I applied Marxist, anarchist, and socially ecological critiques to Dune, The Overstory, and Ex Machina, highlighting how the world-building in these fictions creates ecologies of determinism and hierarchy.

I also drew on the work of literary theorists, Mark Fisher and Eugene Thacker, to show that horror and weird fiction can challenge the hierarchical structure and order of capitalist nature, using examples by adrienne maree brown, Stephen Graham Jones, and Spencer Nitkey.

Lastly, I discuss some examples of dialectical natures, using Murray Bookchin's theory of social ecology as a lens through which to interpret the nature of McBay's 'Inversion' and Wanqing's short story, 'The Peregrine Falcon Flies West’

The paper is open access and freely available for anyone to read.

Something you can do: Extinction Rebellion

What it is: A decentralized, international movement aimed at persuading governments to act on the climate and ecological emergency.

What they do: Take direct action and use civil disobedience strategically to raise awareness, cause disruption, and force governments to act.

Why you should join: They're a highly visible group causing meaningful disruption. Sometimes this gives them a reputation of doing more harm than good, but there's research to back up the fact that this kind of political activism is incredibly effective.

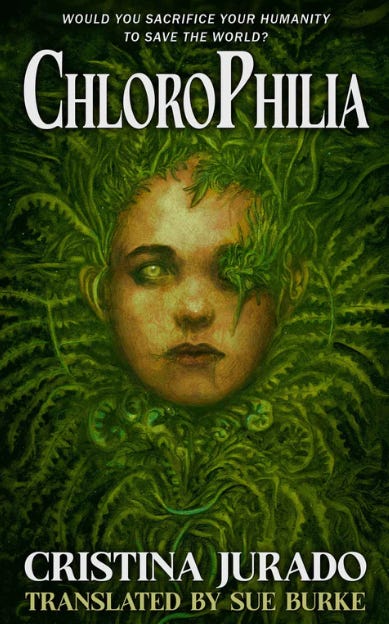

Eco-fiction Review: Chlorophilia by Cristina Jurado

My latest Eco-fiction read was Cristina Jurado's novella, Chlorophilia. Jurado is a Spanish writer, and the version of Chlorophilia that I read was translated by Sue Burke, published by Apex Book Company. And what none of those details reveal is how unusual this book was. I don't think I've read anything quite like it.

The plot centers a character named Kirmen, in a future society that lives in environmental domes that block a destructive wind that sweeps the planet, following a vague environmental catastrophe. Humans are losing their ability to reproduce, and Kirmen is one of the youngest members of society. He's also a genetic experiment, undergoing some kind of metamorphosis that will presumably allow him to live outside of the domes.

What's interesting about the story is that although it has all the traditional sci-fi tropes (post-apocalyptic setting, genetic/environmental engineering, etc.) it's at the same time very much a personal story about Kirmen's experiences, his relationships, and his changes. Jurado uses these narrative techniques to explore big questions about what it means to be human, and what "human nature" is.

Chlorophilia weaves between past and present, introducing a nostalgia for the nature that’s on the verge of disappearing. It's a story about loss, both personal and ecological, and is another short and worthwhile read.

A quick look ahead

Next week's newsletter will be the next essay in my ongoing series, Ecologizing Society. This essay will cover the concepts of degrowth and degrowth communism. Become a paid subscriber so you don't miss it!

Ha! I was searching for “ChloroPhilia” in Apple Books and all that came up was another eco-fiction book called “Chlorophobia”.

Which is a more eco friendly form of providing internet to the globe? Undersea cables all over the ocean floor and cell towers 1000x more numerous than satellites dotting our land (each requiring power and other ground infrastructure), or 1000s of satellites in LEO? There’s money to be made because there’s still billions of people without access to internet. Or is connectivity not something to be aimed for?

Genuinely curious