The Eco-Update #14

Dispatches from the planet.

Urban trees have benefits, but only if everyone gets them

Urban tree canopy, or UTC, is the percentage of urban land covered by tree canopy. It's a useful ecological metric that can be measured remotely with satellite data, and which has health and societal implications.

Given the many benefits to increasing urban tree canopy, many cities are setting UTC targets. A recent study evaluated these targets along with the challenges and benefits that come with them.

Researchers found that while many cities have ambitious UTC targets, careful considerations of how to meet those targets are often less considered. Characteristics of urban forests such as species compositions, spatial distributions, and long-term maintenance should be incorporated into tree canopy target plans.

These factors are especially important when considering a separate recent study of UTC distributions across 370 U.S. cities.

In this study, the authors looked specifically at racial inequalities in the distribution of tree canopy throughout the cities. They found that Hispanic and Black city residents have the lowest exposure to UTC, compared to White residents. What's worse, they found evidence of racial inequality in UTC exposure in 90% of the cities they examined.

The fact that UTC exposure decreases chronic health problems, promotes physical activity, is associated with better mental health, improves air quality, and provides economic benefits makes it clear why these inequalities are a problem.

Furthermore, the study highlights the need for UTC targets to directly account for racial disparities in targets and current levels of UTC.

The Space-For-Time Substitution Problem In Ecology

Climate change impacts ecosystems in many ways, from the ways that they function to the species that comprise them. Because humans rely on ecosystem services, being able to predict what effects climate change will have is critical for ensuring society continues receiving those benefits.

One of the ways scientists make these predictions is what's called "space for time substitutions". Climate change is a relatively recent phenomenon, meaning we don't have long term data on what its impacts have been in order to base predictions on. Space for time substitutions attempts to solve this problem by studying ecological responses along a climatic gradient, using warmer areas to represent future times in cooler areas.

Although this method is common in ecological studies, a new article published in Nature Climate Change argues for more caution in its use. The authors point out to assumptions implicit with the space for time substitution framework.

The first assumption is one of causality. Substituting space for time assumes that climate is the sole or determining factor in the ecological response being measured, which is often not the case. Many factors contribute to an ecosystem's function and structure.

The second assumption is that ecological responses occur immediately after a change in the climate. This is also rarely a valid assumption. Lag times between a change in climate and a corresponding ecosystem change can vary widely.

Violating these assumptions leads to predictions that are inaccurate, sometimes in both magnitude and direction. For example, predictions of Ponderosa Pine growth based on space for time substitution suggested that growth would increase under warmer conditions, but the opposite is true.

The authors present a framework for conveying uncertainty around predictions from space for time substitutions, but the study also highlights the complexity of ecological systems. There's still much we don't know, and this often complicates making accurate predictions. It's one of the many reasons we need much more funding for science, rather than the attacks and cuts currently coming from the US federal government.

In The News

The US Department of Energy released a bogus and false "report" on the impacts of greenhouse gases

The Whale Poop Loop at the foundation of ocean life and the planet's oxygen

Earth's oceans may be undergoing a fundamental and dangerous change in temperature

Pesticides contributed to a mass die-off of Monarch butterflies last year

The New York Times recently sold their articles to Amazon for $20M to train AI models, and they're still charging as much as $25 a week for a subscription. A paid subscription to Brief Ecology is only $5 a week (or $50 for the year), and it's 100% AI-free. Subscribe today to support real journalism.

Something You Can Do: 🔗 Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee

What it is: EWOC is a program that provides logistical support for workers who want to organize their workplace.

What they do: The program trains and guides workers, helping them establish organizing committees and taking the first steps toward forming a union.

Why you should do it: Unions make the workplace safer, more democratic, more environmentally responsible, and better paying. Every worker should have a union, and EWOC can help make it happen.

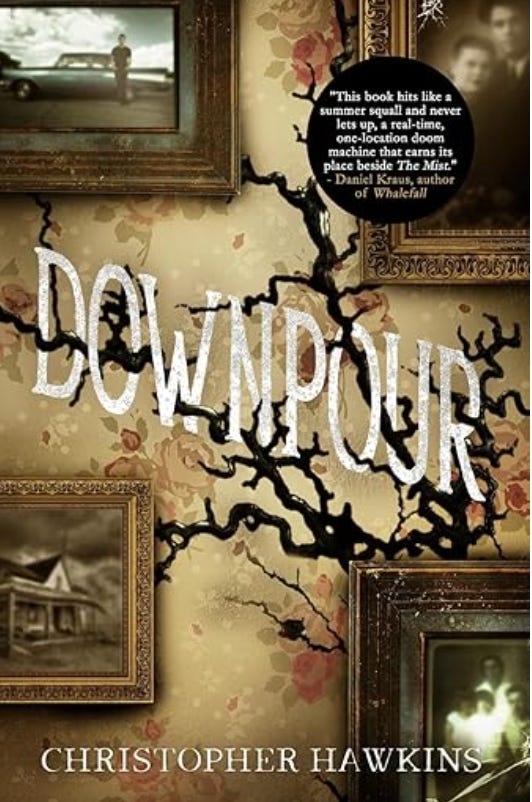

Eco-fiction Review: 🔗 Downpour by Christopher Hawkins

There's something in the rain. My most recent read is Christopher Hawkins's 2023 novel, Downpour, which is a claustrophobic tale of family, trauma, eco-horror.

When an ominous rain cloud forms over the rural house of Scott and his family, the literal and metaphorical deteriorations that come with it reveal the fractures of Scott's past and current family. The narrative of Downpour is a continuous, unbroken timeline from the moment the storm arrives to its final culmination. The entire story takes place over a matter of hours and it never leaves the setting of the rural farmhouse, and in this way, Hawkins traps the reader in the rain with his characters.

As the storm worsens, the rain's unnatural effects begin to emerge. What appears is fungal-like, an invasive, tendrilous entity that seems to dissolve and/or remake everything it touches. It bears similarities to what Dawn Keetely calls tentacular ecohorror, in her essay on ecohorror and tree agency. Whatever is in the rain entangles the characters, mixing their human nature with an unknown and non-human nature, with unknown and non-human agency. The effect is an uncanny, unknowable version of nature that is both within and external.

Downpour is both slow and fast. It's dark, and the story only descends into more bleakness as it goes, until, like the fungal growth in the rain, it spirals in on itself and blooms into something strange and horrifically fascinating. It's a compelling read, but not one for the faint of heart. Nevertheless, I thoroughly enjoyed it.

BTW, UTC canopy disparities are very much at the forefront of most tree planting orgs, grant proposals, UG master plans, etc. Political games and lack of budget for establishment get in the way of implementation.