The Eco-Update #15

Dispatches from the planet.

Forest management and ecology depends on forest ownership

There's growing interest in forest management approaches that emphasize the multiple benefits (timber, carbon storage, freshwater, pollution mitigation, recreation, etc.) that forests provide. Governments and universities are funneling considerable resources into research that examines how to manage forests for these multiple purposes. But what they often fail to account for is that the fate of forests, and the extent to which they can deliver any services at all, depends on who owns them.

Researchers in Czechia performed a nationwide analysis of municipally-owned forests. They found that the majority of these municipalities often seek a balance between market and non-market based uses. In fact, most of the municipalities in the study prioritized environmental and recreational benefits over those that solely generated income.

Similarly, a study of US urban forests in the cities of Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York assessed how ownership influenced spatial characteristics like woodland patch size. Urban forests on municipal land had the lowest forest edge to core ratios, which is a measure of contiguous forest where low values often correspond to higher biodiversity and lower disturbance presence. Conversely, however, fragmented forest patches can provide greenspace benefits to a wider geographic area across a city.

While private forests are subject to the whims of private owners (which often prioritize profit), what these studies reveal is that municipal ownership is an effective form of collective ownership that can more flexibly manage forests to meet multiple needs across different spatial scales.

Plant mutualisms

The majority of ecology and evolution research focuses on the relationship between species and their environment, and how different species compete with one another. Comparatively little attention has been paid to the mutualistic (beneficial) relationships species form with one another or how those relationships shape ecological and evolutionary dynamics.

A recent study published in New Phytologist provides a review of existing literature examining plant mutualist relationships. The study examined several forms of mutualism, including pollinator, mychorrizal and nitrogen-fixing relationships. Synthesizing known patterns provided strong evidence for a "mutalism filter", or in other words, the degree and characteristics of mutualist relationships influence many biogeographic patterns across time and space.

This study not only reveals the importance of mutualism throughout Earth's evolutionary history, but places it as equally influential as competition and abiotic relationships with the environment. It also provides a framework for ecologists to test new hypotheses about mutualistic relationships and the ecological dynamics they contribute to.

In the news

Hey, thanks for reading Brief Ecology. Here’s a free e-book of eco-essays

Something you can do: 🔗 Leave a public comment on the DOE’s false “climate report”

The U.S. Department of Energy recently released a climate "report" that is full of cherry-picked data, misleading claims, and outright lies. Scientists are currently working hard to put together a counter report that highlights all the ways the DOE is misleading the public. In the meantime, the DOE's report is open for public comment. I encourage you to submit a response letting them know that you do not approve of their attempts to sow doubt over the well-established scientific consensus of anthropogenic climate change. You can submit a comment here

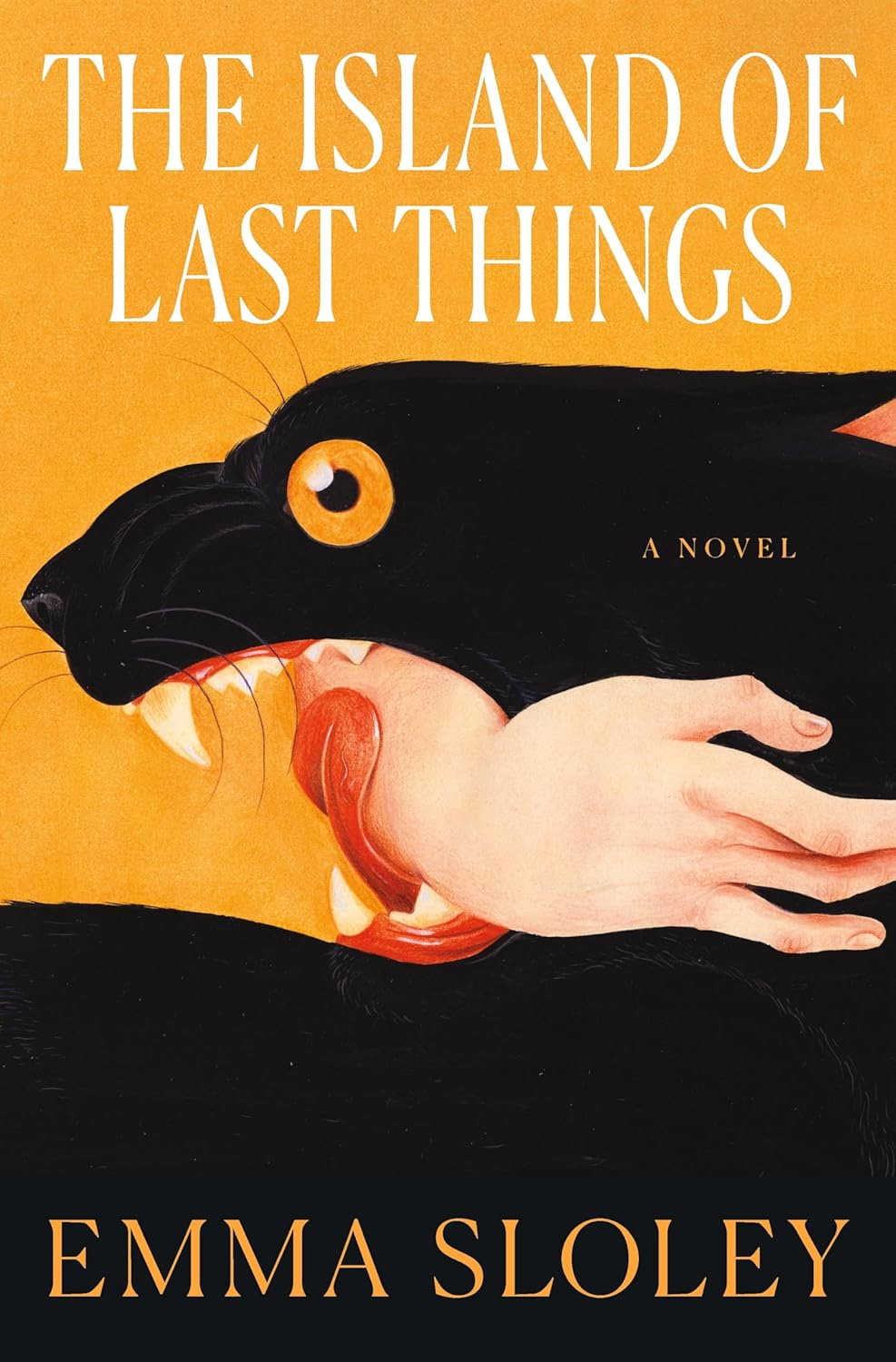

Ecofiction review: The Island of Last Things by Emma Sloley

This week I read Emma Sloley's new book, The Island of Last Things, and I've got a lot of complicated feelings about it. I'll try my best to articulate why this book did not work for me.

First, I'll start with what I enjoyed. The book's premise drew me in, with a story that's centered around the last zoo in operation, which is located on Alcatraz Island, set against the backdrop of a near-future dystopia. In this near future, a combination of climate change and disease has killed off the majority of the planet's life (presumably, but more on that shortly), and the zoo on Alcatraz host last remaining individuals of many species. It's an incredibly intriguing concept to explore the–literally–existential dread of extinction, the ways that human fates are tied up with those of other species, and the ways that our current systems create these issues.

But The Island of Last Things is not about any of that. The plot focuses on the friendship of two zookeepers (Camille and Sailor) who have somewhat contradictory personalities. Which isn't necessarily a criticism by itself. It's perfectly reasonable to foreground a more personal story against the apocalyptic background, which is (I think) what Sloley was attempting. The book does not, however, accomplish that task. At least not in my opinion.

The biggest issue I have with this book is that it seems to contain a current of misanthropy under the surface. Camille and Sailor (and pretty much all the other zookeepers, to the extent that any of them appear on the page) have an overwhelming, almost fanatical obsession with animals, which at times overlaps with their ambivalence or outright disdain for other human beings.

One of the background elements of the book is that the zoo is subject to attacks from political activists who (quite understandably) object to the outrageous expenditure of money to keep a few animals alive and comfortable while humanity starves and suffocates in a deteriorating environment. The characters occasionally discuss this, referring to them as terrorists or otherwise unstable people. At one point in the novel, Camille (a somehow naively cynical person who believes strongly in preserving the status quo) laments that while she understands the plight of these people who are suffering, she simply doesn't think about it much because she doesn't have to see it. She only cares about animals because that’s what she sees.

This misanthropy allows the characters to casually dismiss the structural problems that created the very conditions that underly both human and animal suffering. They pay some thin lip service to "late stage capitalism", without ever interrogating that thought more closely, or doing anything about it. In fact, the extent of the book's "radical action" is Sailor's (the "action" person) idea to free animals from the zoo into the wild. Setting aside the fact that the whole reason the animals are in the zoo in the first place is that the rest of their species died in the wild, the ultimate conclusion of this plan is somehow even more nonsensical. But I won't spoil it for those who do want to read the book.

If I'm being harsh it's because I believe these ideas to be very harmful in their inability to offer a critique of our current system, instead succumbing to a bleak fatalism in the acceptance that nothing can be done, and therefore only solace is to escape into an internal world of numbness and submission.

There are other issues I had with the book too. Thinly developed characters, inconsistent plot elements, and a length that could have been cut down substantially all frequently took me out of the reading. Perhaps the most telling part of the novel was when Sailor implores Camille to "imagine a better world", the irony being that there is clearly not a better world on offer anywhere in the book.

I've been meaning to feature your work on my McAllister's Mates series -https://www.graememcallister.com/t/reviews (a collection of reviews on articles and writers I found to be enjoyable and inspiring). This one is perfect - it gives a real overview of your work as a scientist and journalist. I think you're doing great work in not only making ecology easier to understand and approachable, but also providing a sensitive, passionate, very human face to science. I'll let you know when it's up.

I know this is a little off topic but I think you would have an interesting insight. What are your thoughts? I am genuinely curious. https://substack.com/profile/345445637-elias-johnson/note/c-147396052