The Eco-Update #19

Dispatches from the planet.

In This Issue

Whose wind is it, really?

Bird biogeography reveals the complexity of desert biomes

A letter from the editor

Eco-Stories In The News

Eco-fiction Review: The Veldt Institute

Something You Can Do: Join DSA

Whose wind is it, really?

By Ben Lockwood

Who owns the wind? Who holds the rights to its movement? Who controls access to it? Who profits from it? These questions are rarely asked in conversations about renewable forms of energy, but are increasingly important as renewables become the dominant form of energy globally.

A new study conducted on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland reveals the ways in which capitalist enterprise is able to capture and extract value from wind. Researchers from Denmark and Norway explored a conflict in Scotland over “wind rights” between a corporate energy developer seeking to extract private profit and a Community Development Trust attempting to retain the energy value within the local community. In 2003, the Stornoway Trust (the largest landowner on the island) made plans to develop a large wind farm that would pay a rent to nearby communities as a benefit.

However, the feudal nature of historical landownership in the U.K. has long prevented community self-determination. To correct this, the Scottish Government implemented reforms that have allowed local communities to take ownership over private land with absentee landowners for the purposes of sustainable development. This allows the local communities to determine the use of land and to also benefit more directly from its utilization. Several small-scale and community-owned wind power projects have been deployed under these reforms, which motivated more communities to attempt the same on land which was owned by Stornoway Trust and already designated for private wind development. This dynamic set off the aforementioned conflict between the local communities, the Stornoway Trust, and the private wind developer.

Ultimately, a court ruled in favor of Stornoway Trust and the private developer, and in doing so prevented the deployment of community-owned wind farms. While this case bears some place-specific dynamics, the authors of the research argue it has general relevance to the economics of wind energy.

“[E]xisting land tenure and land ownership structures matter for both the utilization of wind energy and distribution of value generated from the commodification of wind,” said Dr. David Rudolph, the lead author of the study.

In the paper, the researchers describe a process of capitalist exploitation over wind rights for profit extraction which they call “wind-grabbing”. The first step in the process is assetisation. This involves turning the land on which wind turbines will be placed into an asset, as private property, which can then become a rent or revenue stream. The second step of wind-grabbing is land and wind enclosure. Landowner property rights both determine and constrain access to the land over which the wind blows, allowing for the enclosure of an otherwise mobile resource. The third part of the wind-grabbing the authors identify is territorial alienation from the wind. Legal rights granted to private landowners prevent local community utilization of the wind for their own collective benefit, thus severing and alienating them from the land itself. Lastly, value extraction from wind is made possible via rent and revenue streams that accrue from both land leasing and the production of wind energy as a commodity.

The authors go on to state that wind-grabbing highlights how local struggles over wind access rights are contingent on land and land ownership. “In the paper we argue that landownership mediates and co-determines who is able (or allowed to) harness the wind resource by deploying wind turbines and how (exchange) value from wind energy is created locally,” said Dr. Rudolph.

Ultimately, this kind of research sheds light on the uneven distributions of revenue extracted from wind energy. The structures of capitalism and historical legacies of landownership often perpetuate unjust relationships between communities and land, and further contribute to imbalances in the received benefits of an otherwise sustainable and renewable form of energy. As renewables become the dominant form of energy globally, close examinations of the structures that determine their beneficiaries are necessary to ensure a more just energy future.

Bird biogeography reveals the complexity of desert biomes

By Ben Lockwood

Researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology in Jodhpur have conducted a new study on avian ecology and biogeography across the world’s major deserts. Using a combination of of crowdsourced bird occurrence data with hydrologic, meteorologic, and vegetation data from satellites, the authors examined the spatial and temporal dynamics of desert bird evolution and ecology.

In the paper, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, the researchers noted that deserts are critical, but under-studied ecosystems. Birds are often used as indicator species for ecosystem changes due to their mobility, visibility, and high sensitivity to environmental conditions. Given these characteristics, the authors of the study used avian ecology as a proxy for the broader responses of desert biomes to climatic changes.

They found contrasting evolutionary patterns between deserts near the Tropic of Cancer and those near the Tropic of Capricorn. Avian ecology in deserts near the Tropic of Cancer reflected more flexible life-history traits, suggesting adaption to more diverse conditions. On the other hand, in deserts near the Tropic of Capricorn avian ecology indicates stronger environmental filters that have selected for more sedentary bird groups capable of enduring year-round conditions.

Beyond this, the authors reported interesting desert-specific patterns. For instance, while temperature and vegetation productivity had strong influences on avian species richness, this wasn’t the case in the harsh deserts of the Gobi, the Great Basin, and the Thar.

“Regarding NDVI [a measure of vegetation productivity], it is not uniformly positively correlated with avian species richness across all ten deserts,” Dr. Manasi Mukherjee, the study’s lead author, said. “Instead, the relationship varies; likely influenced by complex interactions among multiple climatic factors. As a result, some deserts may show stronger links between primary productivity and richness, while others do not. This highlights that greening or enhancing primary productivity alone may not be a universal or sufficient conservation strategy for deserts.”

Ultimately, the study highlights that predicting future changes in desert biomes requires understanding the unique and location-specific biogeographic contexts of individual deserts.

Dr. Mukherjee said about the work, “Our study underscores the importance of integrated assessments that combine environmental and biotic data to provide nuanced insights for conserving desert biodiversity and ecosystem services amid accelerating climate change.”

Letter From The Editor

Dear Reader,

Legacy media continues to bend the knee to authoritarian censorship and billionaire interests. The Eco-Update by Brief Ecology remains a free and independent source of environmental and ecological news. Support from regular people like you helps it stay that way for everyone. For only $5 a month you can help keep the lights on, the coffee brewing, and the words flowing.

Thanks,

-Ben

Eco-Stories In The News

NPR: Renewable energy outpaces coal for electricity generation in historic first, report says

BBC: Green turtle bounces back from brink in conservation ‘win’

Eco-Fiction Review: The Veldt Institute by Samuel M. Moss

By Ben Lockwood

Let us contemplate the nature of being in the veldt. Let us contemplate the nature, of being, in the veldt. Let us contemplate, the nature of being in the veldt. I recently read Samuel M. Moss’s The Veldt Institute, from Double Negative, and I’m still thinking about it.

First, let me address that categorizing this book as eco-fiction is...debatable. However, I think it’s justified given that the word “veldt” refers broadly to open and homogenous grassland landscapes; imagery that does play an important role throughout the novel. The plot (if there can be said to be one) follows an unnamed narrator who is a patient at a mysterious kind of wellness center known as “The Veldt Institute”. We follow the narrator throughout his or her courses of treatment as they progress through the care of the various doctors and prescriptions at the Institute, and things become increasingly detached, philosophical, and metaphysical.

One coincidence that enhanced my enjoyment of this book is that I happened to read it at the same time I was reading George E. McCarthy’s Shadows of the Enlightenment, which I reviewed last week. Reading both made for a kind of dual exploration on the nature of meaning and knowledge. Moss’s novel feels like a contemplation on meaning itself, an attempt to describe an idea larger than language. In fact, the entire story could function as a metaphor for a journey inward toward some unreachable understanding of everything: The entire meaning of the universe.

It plays with ideas of eternal return, infinity, thought and knowledge, and many other things. If you like cerebral, contemplative reads that stick with you long after finishing, I can’t recommend The Veldt Institute highly enough.

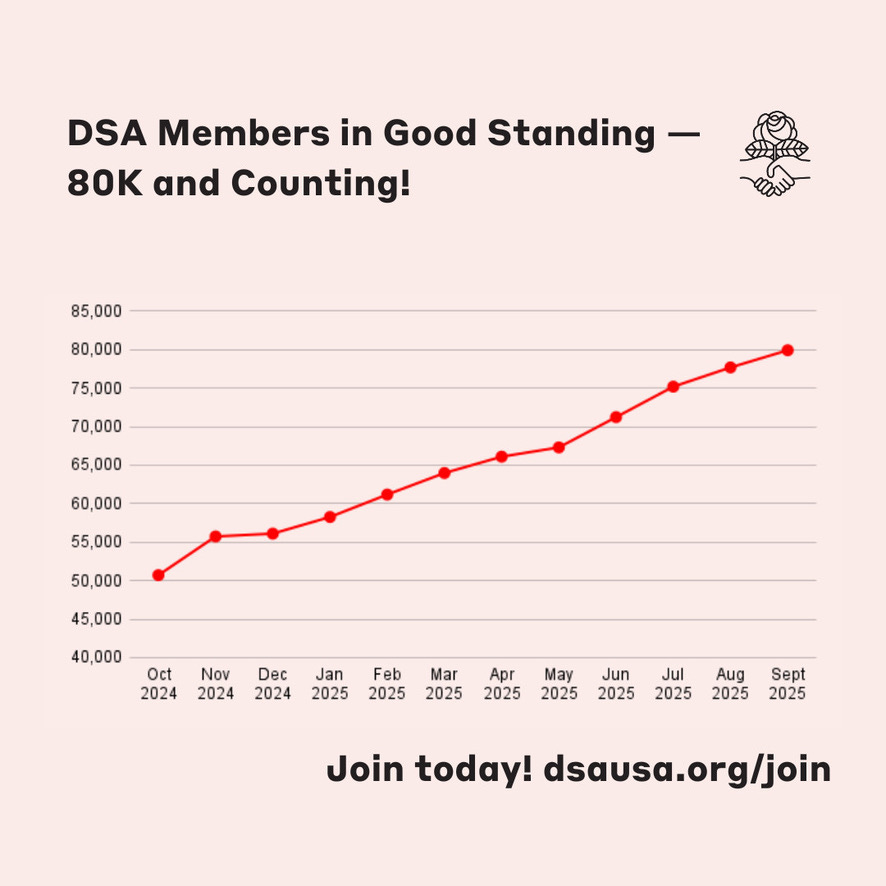

Something You Can Do: Join DSA

I’ve talked about them before. The Democratic Socialists of America are among the fastest growing political groups in the United States. As capitalism transforms into fascism before our eyes, people are recognizing that a socialist future is brighter, kinder, more just, and more livable than the totalitarianism we have now. Join DSA and help make that future a reality.