The Quiet Persistence of Clubmosses

by Susan Shea

The following is a guest essay provided by Northern Woodlands Magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org. Be sure to subscribe to Brief Ecology for more ecological writing and essays!

The Quiet Persistence of Clubmosses

By Susan Shea

Walking in our woods in early winter, I notice dense patches of clubmoss that lend a welcome splash of green to the forest floor. Some of these evergreen plants resemble miniature Christmas trees; others have fuzzy runners that creep across the ground.

Despite their name, clubmosses are not true mosses. They are the oldest group of vascular plants, which have specialized tissue called xylem that transports water and nutrients. Clubmosses evolved 410 million years ago and dominated the forests of the Carboniferous Period (roughly 350 to 300 million years ago), when they could grow up to 100 feet tall. Coal deposits contain the remains of these ancient clubmosses.

Today’s clubmosses are small herbaceous plants with shiny, needle-like leaves called microphylls. Their name comes from their resemblance to mosses and their club-like reproductive structures, called strobili. Strobili grow from the tips of erect stems and disperse spores. The dust-like yellow spores were used for flash powder by early photographers. Because of their high oil content, they give off a flash when ignited. Plants can spread vegetatively through horizontal stems that creep along the ground, or through subterranean rhizomes.

Clubmosses grow in woodlands, on forest edges, in bogs and swamps, and in brushy fields. Different species prefer different soil types, ranging from acidic to nutrient-rich and from moist to dry. Six different genera, or groups, of clubmosses are found in New England, containing about fifteen species.

Prickly tree clubmoss (Dendrolycopodium dendroideum) is a common species that looks like a row of small conifer trees. Vertical stems arise every six inches from underground runners. The upright stems have many branches, with dark green microphylls that are prickly to the touch. Yellow-green strobili that contain the spores grow singly from upper branches. Prickly tree clubmoss is closely related to princess pine, once widely harvested for holiday decorating.

Southern ground cedar (Diphasiastrum digitatum) is another common species, though it is quite different from the tree clubmosses. Its yellowish-green vertical stems have flattened, fan-like branches with tiny, scale-like leaves that resemble those of a cedar bough. The yellow strobili rise in candelabra-shaped clusters of two to four from stalks that grow off the upper branches.

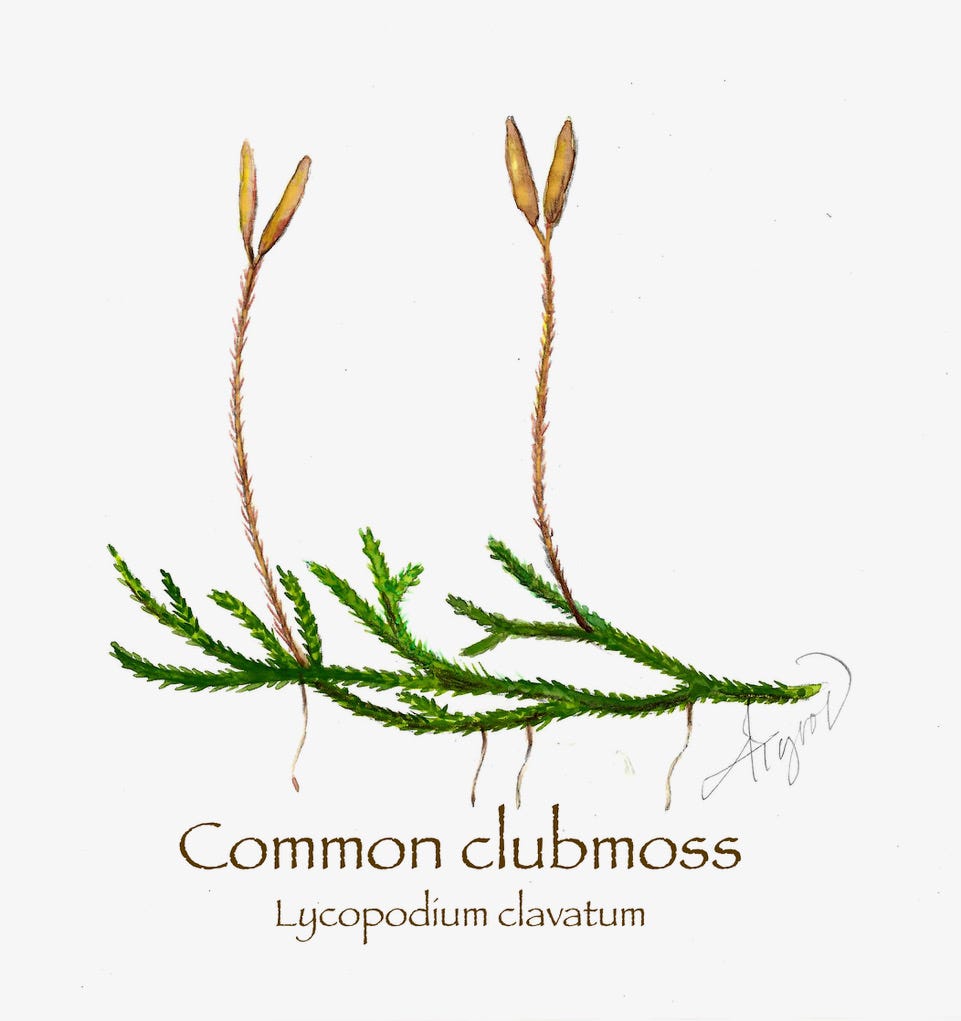

Common clubmoss (Lycopodium clavatum) is not tree-shaped like the last two species. Its fuzzy, green erect stems grow from horizontal rhizomes that trail across the surface of the ground, often interlacing to form dense colonies. One to five strobili grow on a stalk from the tip of each vertical stem.

Like their fern relatives, clubmosses undergo two very different developmental stages during their lives (sometimes called alternating generations). There is a gametophyte, or sexual, phase, and a sporophyte phase, the spore-producing phase. When a spore lands in a suitable moist spot, it develops into a gametophyte: a flat, green, heart-shaped body with sex organs that grow underground. When stimulated by water, sperm from one gametophyte can swim to the female organ on another gametophyte and fertilize an egg. The egg divides and grows into a tiny clubmoss, a new sporophyte, at first anchored to the gametophyte. While the gametophyte phase is tiny and hard to see, once a sporophyte develops, it becomes recognizable to us as a clubmoss. The complete life cycle, from spore to gametophyte to sporophyte, can take up to twenty years.

Clubmosses play an important ecological role on the forest floor. Mats of clubmoss hold soil in place, preventing erosion, especially on slopes. They maintain soil moisture and reduce temperature fluctuations, creating a stable, sheltered microhabitat for fungi, microorganisms, invertebrates, and small animals. Clubmosses contribute to nutrient recycling in the forest. As their dead leaves and stems decompose, they release essential plant nutrients back into the soil. Species that colonize disturbed areas can improve the soil, facilitating the growth of other plants.

I’ve wondered why clubmosses are abundant in some woodlands, like ours, and not in others. This is likely determined by soil type and past land use and disturbance history, including whether they were harvested for Christmas displays. Because clubmosses are so slow to reproduce, collection can deplete local populations. This practice is now banned or requires a permit on many public lands.

It’s best to enjoy these unique evergreen plants in their natural habitat and appreciate the color and diversity they add to the winter woods. In their quiet persistence, clubmosses remain living links to Earth’s first forests.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer, and conservationist based in Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.

Thank you, I had never heard of clubmoss! I will see if there is anything similar in UK woodlands!

This was excellent - thank you. I love that they are the oldest vascular plants. A small view into the evolution of the past!