From Soil to Sky

The Eco Update #24

What’s in this issue

Letter From the Editor

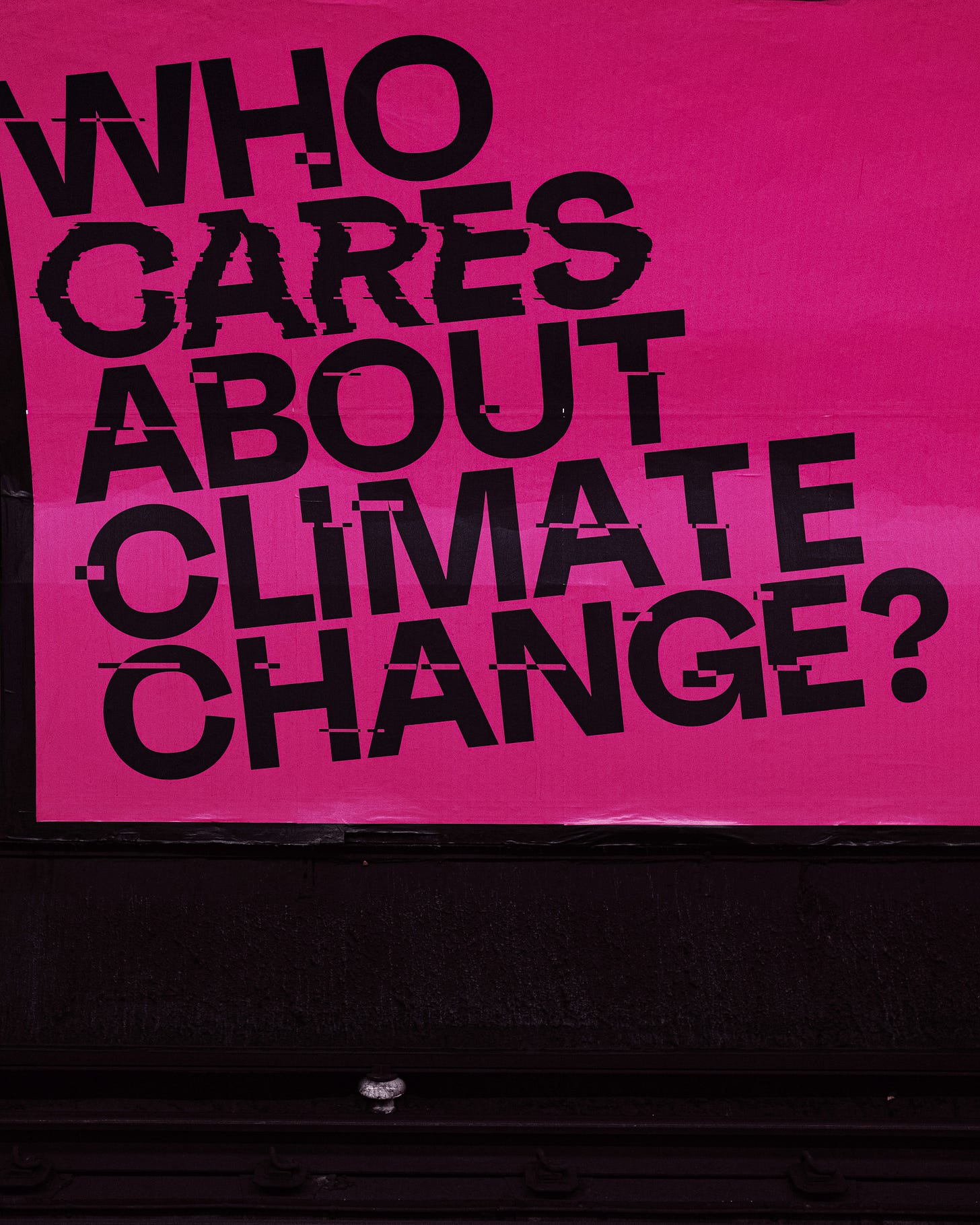

When Climate Speaks English by Dr. Anh Ngoc Vu

Agroecology in the City by Ben Lockwood

Notes From a Radical Ecologist | Relearning Terra Preta as a Living Method for Zero-Waste Soil by Noel L. Alonzo

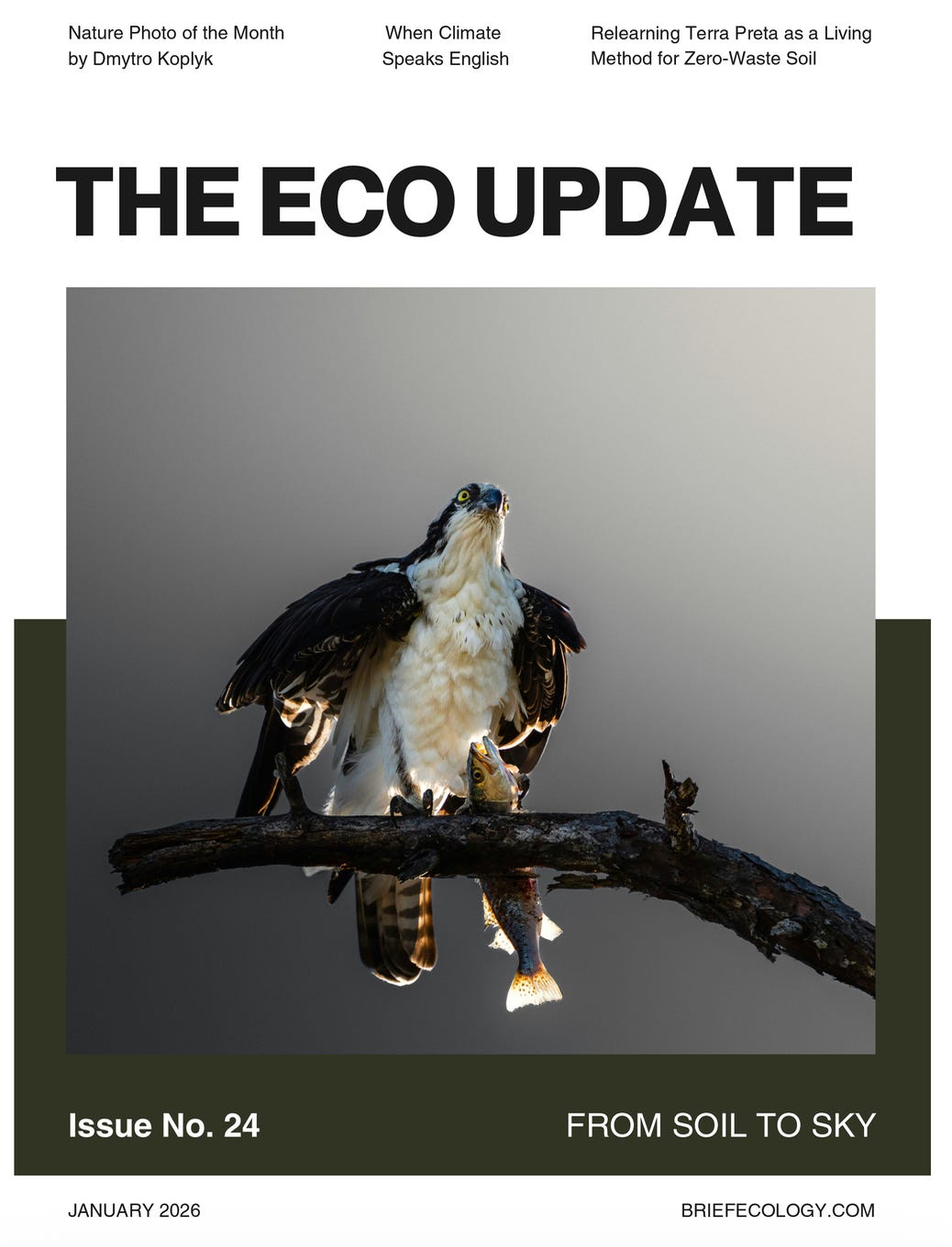

Nature Photo of the Month by Dmytro Koplyk

Eco Fiction Review | Origins of Desire in Orchid Fens, by Lynn Hutchinson Lee

More from Brief Ecology this month

Letter From The Editor

Readers,

We are living through dark times, but that doesn’t mean we can’t still find things to inspire us. There are some new and very exciting things coming to Brief Ecology.

First, you may have noticed some changes to this issue of The Eco Update. Specifically, you might think that it looks kind of like a magazine. That’s because it is. The Eco Update is now a monthly periodical featuring original news, essays, and photography. It’s also available as a fully downloadable digital magazine, but more on that shortly.

What does all this mean for The Eco Update newsletter? Nothing. It’s still going out to all Brief Ecology newsletter subscribers via email, it’s still entirely free to read, and it’s going to stay that way. It’s just that it is now also available as a digital magazine with some glossier design elements.

So how do you get your hands one of these fancy digital copies? The first issue is free, on us. Soon, we’ll have a completely re-designed website where digital copies will be available under a pay-whatever-you-want (even $0) model.

Brief Ecology continues to grow, and we’ve got some big things planned for this year. So stay tuned and, as always, thanks for reading.

In Solidarity,

Ben

When Climate Speaks English

by Dr. Anh Ngoc Vu

Most of the world’s climate research is written in English. That might seem practical, but it comes with a cost: whole bodies of knowledge produced in other languages—often from the Global South—are ignored. In a new paper in Area, we ask a deceptively simple question: does the language of research actually change what we know?

To find out, we compared two “systematic evidence reviews” (SERs) on the same topic: the health impacts of climate change on outdoor workers in urban Asia. One review searched only English-language studies; the other searched Vietnamese-language sources using the same methods. What we found was striking. The two bodies of literature did not simply repeat each other. Instead, they told different stories about climate, health, and responsibility.

Two reviews, two worlds

The English-language review drew on large international databases and focused on cities across Asia. It tended to frame climate change at a macro level—looking at long-term risks, heat waves, and population-scale outcomes such as mortality or hospital admissions. These studies often emphasised structural drivers of vulnerability, such as poverty, gender, migration status, and weak labour protections. Their proposed solutions leaned toward system-level change: urban planning, heat-health warning systems, labour regulations, and policy reform.

The Vietnamese-language review, by contrast, focused almost entirely on Vietnam and on specific groups of formal workers—sanitation workers, traffic police, construction workers. Rather than using abstract health indicators, these studies described everyday illnesses and bodily strain: dizziness, urinary disease, digestive problems, musculoskeletal pain, and fatigue. Climate was framed less as an extreme event and more as part of daily “weather” that shapes working life.

Most importantly, the Vietnamese studies emphasised individual coping strategies: protective clothing, hydration, posture changes, dietary supplements, exercise, and rest. Responsibility for adaptation was often placed on workers themselves, rather than on employers or governments.

Why do these differences matter?

If policymakers rely only on English-language research, they may assume that climate vulnerability is best addressed through large-scale policy and infrastructure. If they look only at Vietnamese-language studies, they might conclude that the problem can be solved through workplace adjustments and personal behaviour. Neither view is complete on its own.

Language does not just translate ideas—it shapes them. Each research tradition reflects its social, political, and institutional context. English-language journals prioritise theory, comparison, and generalisation. Vietnamese outlets write for national audiences and are shaped by different political constraints and academic norms. As a result, the two literatures sit in separate “knowledge silos,” rarely speaking to one another.

The bigger picture: epistemic justice

Listening across languages will not magically solve climate injustice. But without doing so, climate science risks remaining abstract, reductionist, and disconnected from lived realities. Workers do not experience “mortality risk curves.” They experience aching backs, dizziness, exhaustion, and fear of losing income if they stop.

Our findings highlight a deeper problem in global climate research. When systematic reviews exclude non-English sources, they appear neutral and comprehensive—but they quietly reproduce hierarchies of knowledge. Voices from the Global South are treated as “local” or anecdotal, while English-language studies are assumed to represent universal truth.

Yet, as this comparison shows, Southern-language research does not simply add detail—it changes the questions we ask and the solutions we imagine. Listening across languages is not a courtesy; it is a necessity for just and effective climate action.

A truly global climate science must learn to hold both perspectives at once: the systemic and the everyday, the structural and the bodily. That begins by recognising that language does not just describe climate change—it decides whose suffering is seen, and whose solutions are imaginable.

Agroecology in the City

by Ben Lockwood, Ph.D.

We are in the midst of a biodiversity crisis. Extinction rates are accelerating, ecosystem functioning is degrading, and public wellbeing is suffering as a result. Given the potential for ecological collapse, it’s vital that we find ways to not only preserve, but enhance the planet’s existing biodiversity.

Urbanization is one of the leading drivers of biodiversity loss as flora and fauna habitat is increasingly destroyed. But urbanized areas also present opportunities. Many cities are adding greenspaces to streets, parks, and rooftops, and emerging research indicates that these greenspaces have a positive impact on biodiversity. But comparatively little is known about the effects of urban agriculture on biodiversity.

A new study published in Innovations Agronomiques conducted a review of scientific studies to synthesize the existing knowledge on how urban agriculture influences biodiversity. For the study, the authors defined urban agriculture as the “growing of plants and raising of animals in and around cities”. They used species richness, species diversity, and species abundance as indicators of urban agriculture’s impacts on three taxonomic groups: plants, birds, and arthropods.

In their review, the study authors came to the general conclusion that larger plots, greater plant diversity, and habitat heterogeneity all positively influenced biodiversity of the taxonomic groups. They found that community and allotment gardens are often rich in biodiversity, and that urban agriculture appears capable of supporting a diverse range of plant and animal species. Overall, the authors state that the evidence supports the claim that biodiversity benefits from urban agriculture.

They did, however, note that considerable variation in these trends is influenced by spatial, environmental, and other contextual factors. Furthermore, the authors highlight that the impacts of urban agriculture on biodiversity have not been adequately studied, and that more systematic approaches are needed more precisely quantify specific relationships.

Nevertheless, this review study illuminates the potential for methods of agricultural production in urban settings that also support biodiversity. Currently, agriculture is dominated by monopolistic, industrialized, homogenized, and destructive practices. Urban agriculture provides an avenue to produce food in highly local and heterogenous ways that may also help mitigate the harmful effects of urbanization.

Notes from a Radical Ecologist

Relearning Terra Preta as a Living Method for Zero-Waste Soil

by Noel L. Alonzo

Modern cities generate an extraordinary volume of organic waste: food scraps, cardboard, bones, ash, and mineral residues; materials typically treated as liabilities rather than ecological assets. At the same time, urban soils are compacted, biologically depleted, and dependent on continuous external inputs to remain productive. This contradiction suggests not a technical failure, but a cultural one: contemporary systems excel at removal, while retention is almost nonexistent.

Terra Preta de Índio, the anthropogenic dark earths of the Amazon, emerged from a very different orientation. Rather than a fixed recipe or lost technology, archaeological and ecological evidence from pre-Columbian sites suggests Terra Preta arose through long-term cultural practices of waste cycling and mineral stabilization carried out at household, village, and possibly citywide scales. These soils accumulated gradually through repeated, ordinary acts of care (i.e. charred biomass, food waste, bones, ash, ceramics, and organic residues returned to place over generations).

What distinguishes Terra Preta is not peak fertility, but trajectory. Unlike most soils, it improves with time. Nutrients are retained rather than leached, organic matter resists rapid decomposition, and biological activity persists even under stress. In this sense, Terra Preta behaves less like a consumable input and more like infrastructure: a carbon-mineral system capable of storing and releasing fertility gradually over years, decades, even centuries.

This essay does not claim rediscovery or replication. Instead, it explores how the principles underlying Terra Preta like carbon permanence, mineral buffering, and biological patience, can inform modern zero-waste soil practices already familiar to urban composters. The emphasis is not on novelty, but on sequence: practices many people already use, applied deliberately over time rather than in isolation.

In contemporary urban systems, organic matter is often decomposed rapidly, nutrients are made soluble, and excess fertility is lost through runoff and leaching. By contrast, a Terra Preta–inspired orientation prioritizes stabilization before breakdown, buffering before release, and biological succession over speed. When composting, mineral additions, and biological finishing are understood as parts of a continuum rather than interchangeable steps, fertility becomes less volatile and more durable.

A critical but often overlooked feature of Amazonian soil systems is the presence of Terra Mulata, a lighter, transitional soils enriched through repeated organic additions but containing less charcoal than Terra Preta. Terra Mulata appears to function as an active cultivation layer, renewed regularly and surrounding more permanent dark earth cores. This distinction matters in modern contexts. Not all soil outputs need to be maximally carbon-dense to be valuable. Fast-cycling biological layers feed and extend the influence of deeper, more stable soils. Terra Preta stores nutrients; Terra Mulata moves them. Both are necessary, and neither functions optimally alone.

This approach is intentionally unsuited to industrial scaling. Its strengths lie in small footprints, low energy requirements, and tolerance for inconsistency. It is designed for backyards, schools, community gardens, and urban tree pits; places where centralized infrastructure is impractical or absent. Used correctly, even small quantities can alter soil behavior, improving water retention, reducing nutrient loss, and stabilizing microbial communities over successive seasons.

Any modern engagement with Terra Preta must acknowledge its origins. These soils are the product of Indigenous Amazonian cultures whose populations were devastated following European contact. The knowledge embedded in Terra Preta was not freely offered, yet it survived colonization and disease through the land itself. For this reason, the work described here emphasizes transparency and teaching rather than ownership. The goal is continuity, not control.

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of relearning Terra Preta is resisting speed. Modern sustainability frameworks prioritize efficiency and rapid outcomes, yet Terra Preta teaches a different lesson: soil becomes powerful when it is allowed to age. Relearning it today may require less innovation than humility, an acceptance that durability matters more than optimization.

Nature Photo of the Month

by Dmytro Koplyk

Want to have your photography featured in an issue of the The Eco Update? Send your best nature photo to editor@BriefEcology.com with the subject line “Photo Submission” to be considered

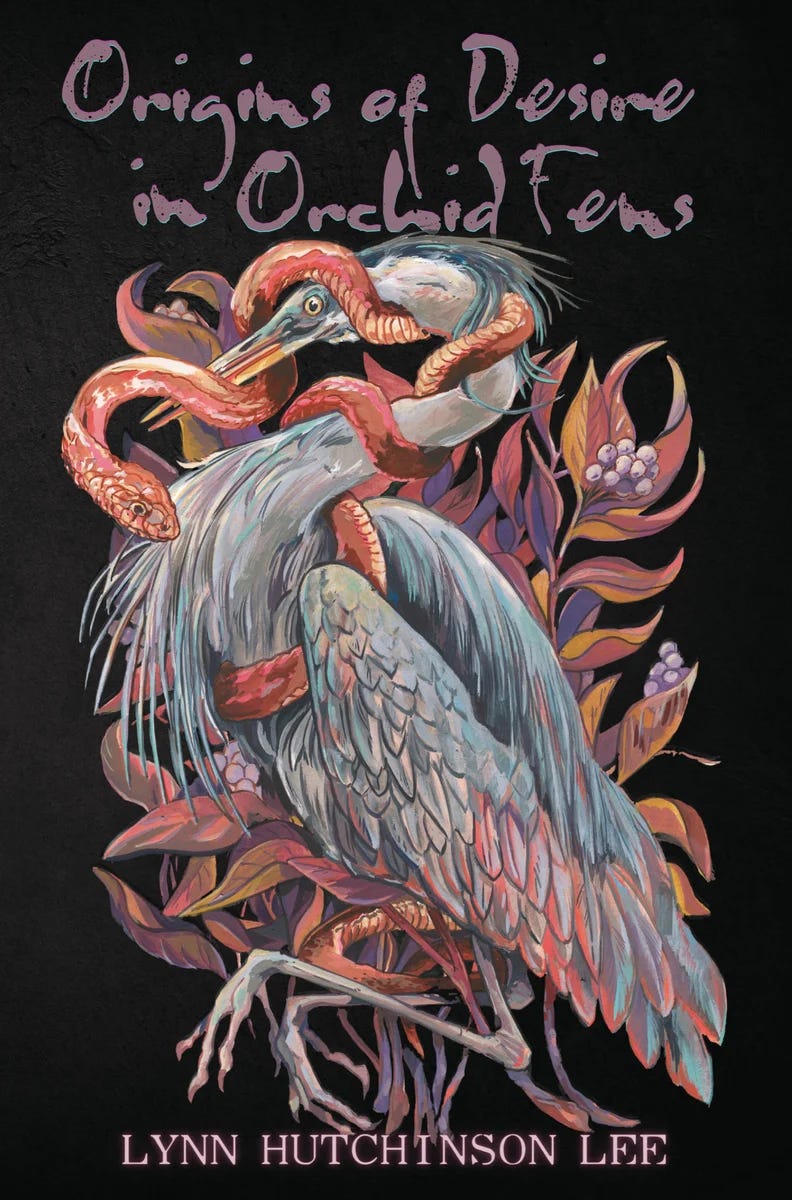

Ecofiction Review | Origins of Desire in Orchid Fens, by Lynn Hutchinson Lee

Review by Ben Lockwood

“The mine batters the men, the men batter the women and children, and the dead take their revenge.”

If there’s a single line that could be said to encapsulate Lynn Hutchinson Lee’s Origins of Desire in Orchid Fens, it’s this one, but this is not an easily encapsulated book. It is, however, one of the most interesting pieces of ecofiction I’ve read in a while.

The story’s narrative centers around a young Romany woman balancing a new marriage with her increasingly prickly and ill mother. The story unfolds amidst the backdrop of a town whose natural (and haunted) wetlands are threatened by a local mining company, which also happens to employ many of the men in that town. Lee develops these conditions perfectly to explore the personal, psychological, financial, and environmental destruction that capitalist exploitation wreaks.

But Origins of Desire in Orchid Fens is much more than that. The book explores themes of prejudice and intolerance of the Romany people, structured and systemic violence against women, mother-daughter relationships, the seductive nature of capital, and a class-based perspective of environmental degradation. There’s so much that I liked about this book that it’s hard to fit it all into a short review.

There was one theme in particular, though, that I kept coming back to while reading. Through the trials and conflicts of the various characters, Lee highlights the often-invisible labor and organizing of women that makes a community. Housework, preparing meals, planning social events, and other domestic work are often gendered, devalued, and relegated to women. And yet, as Lee reveals, these very activities are what hold a community together during times of struggle.

Just as the conditions of the story are complex, so too are the characters. They have flaws, they make mistakes. Some of the men of the town commit violence, but some of them are also driven by love, and they ultimately band together in a radical, collective labor movement. It’s not the men who get the final say though. The women (dead and living), while just as complex and flawed, are the drivers of the narrative here.

On top of all this, Lee delivers the story in a sharp, literary style. Experimenting with both voice and form, she crafts a unique and engaging story of romance, horror, hauntings, community, ecology, violence, and perseverance. I really can’t recommend this one highly enough.

More from Brief Ecology this month

When the Ghosts Come Tumbling In, by J.S. Douglas | The Rotting Leaf

Life Beneath the Ice and Snow| The Outside Story

Making Ecosocialism Irrelevant? | Ben Lockwood

J.S. Douglas on Ecofiction | The Rotting Leaf

Want to support Brief Ecology without becoming a paid subscriber through Substack? We’ve launched a GoFundMe to raise some funds that will help us grow and make everything we publish free to read.